Alan Temperley writes a blog post for us about his time as an English teacher in Farr Secondary School and the creation of a fantastic collection of tales, told by his pupils. We’d like to thank Alan for writing this and for his patience.

A Surprise Success

For eight years, from 1965 – 1973, I taught English at Farr Secondary School in Bettyhill, on the north coast of Sutherland. They were among the happiest years of my life. I was twenty-eight when I arrived, old for my first teaching post. This was because on leaving school aged sixteen I had spent several years at sea but realised that what I wanted more was to study English, which led in time to National Service in the RAF and then the years of university and college.

For eight years, from 1965 – 1973, I taught English at Farr Secondary School in Bettyhill, on the north coast of Sutherland. They were among the happiest years of my life. I was twenty-eight when I arrived, old for my first teaching post. This was because on leaving school aged sixteen I had spent several years at sea but realised that what I wanted more was to study English, which led in time to National Service in the RAF and then the years of university and college.

Farr was a Highland school with about fifty pupils in the secondary department. Those who passed the eleven plus went mostly to senior secondary school in Dornoch but some remained, for parents did not always want their children to leave home at such as young age. Farr did not present for the national exams which meant that we teachers were enabled, with approval, to teach what we felt would be most valuable and interesting.

In English my pupils had to become clear, confident and accurate in speech, writing and reading, that before anything else, and all was directed to that end. But the lack of a national curriculum gave us a huge freedom. I ordered novels in small sets and gave groups their choice. They wrote and illustrated short story collections on themes of their own choosing and took them home to be read, all in longhand those days. They kept poetry jotters, wrote their own and occasionally won awards. They wrote plays which were performed at concerts. They talked, they debated, they acted.

And we went out a lot; the school became known for it. On stormy days we climbed the Aird above the village to be beaten by the wind, make notes and return to write it up. Or we might walk to the crashing rocks and seashore. In the snow we built igloos. Every year we waded to the island to be dive-bombed by the nesting terns. We went to the pastures at lambing time. We sought settings for stories, and at weekends, when they attempted the first of several joint-effort novels, I drove pupils quite long distances to explore real locations. All, in one way or another, spoken, written, acted or illustrated, ended up in the classroom. I think they enjoyed it and visiting inspectors, to whom I really gave little attention, gave my headmaster good reports.

I also taught Geography and on one occasion the children, who came from every village and clachan, carried out a major social survey, house by house. The residents were grouped by age, whether they worked locally, ran a croft, had a car or telephone, cut peats, were employed by the oil industry, Dounreay, the forestry, the county, and so on. They wrote about the importance of these industries and employers, their personal hopes and plans and daily lives. It was a good piece of work which through a colleague came to the ears of a geographer in Edinburgh who at that time was preparing a major new three-volume series for use in schools. Much of our project, happily, became incorporated into the chapter on the Scottish Highlands.

As a side-issue, possibly from old folk in their villages, I asked pupils to collect tales of the old days, historical tales of battles, murder and sea tragedy, factual accounts of killing a sheep or building a house, stories of ghosts and fairies, second sight, illegal stills, press gangs, poaching, grave robbers. The idea spilled over into my English classes and so many came in that I thought of making a collection of thirty-two or sixty-four pages, written by the children, corrected by me, illustrated by them, for sale locally and to tourists.

The longer we worked, the more stories came in – and alternative versions of the same story. All were at different stages and in time, long before the collection was ready, too many pupils got fed up: “Oh, sir, can we not do something else?” Of course we were doing other work but in the end I was forced to accept that for the moment, at least, we could do no more and the stories were tidied away.

The following year I resurrected them but although the children worked very well and the collection kept growing, I was never happy that they were ready to present to the public. Perhaps I was too demanding; after all, these were pupils in a small Highland school. But the stories were good and deserving of the best treatment. Anyway, a third time I attempted but the result was the same.

Then I left the school. I had enjoyed it enormously and I hope had done well by my pupils but after eight years my energy was running out, I needed a change. But what was to be done with the stories? I spoke to the headmaster and the pupils: we couldn’t just throw them out, so should we pass them to some person in the community? Leave them for my replacement? What was decided was that I should take over the collection myself and, whilst retaining the children’s words as far as possible, attempt to do something with it.

And so I did. Living now in Galloway I worked on it for eighteen months, surviving financially by spells of temporary teaching. I edited the stories in pencil and typed them. Rewrote and retyped. Reorganised. Extended. Added a section on the ruthless Strathnaver clearances in the words of historians and people who were evicted Drew maps. Rewrote again. And knowing nothing about publication, approached every body I could think of: publishers, the Scottish Arts Council, other Scottish associations, agents. Extracts, background, synopsis. Nobody was interested. Stories by schoolchildren from a small school in some distant corner of the Highlands and their ill-informed English teacher, why should they be interested?

In the end, disheartened, I went back to sea: trawlers, AB on oil rig supply ships, deck officer deep sea. And when my ship returned from New Zealand, waiting for me was a three-months’ old letter from the Research Publishing Company, a small London publisher who had heard about the stories and wished to see them. So I hung my uniform in the wardrobe and at once, refreshed, set about reorganising them. For many months longer I worked on them, trying all the time to get him to see the collection as I did and persuade him to publish. On one never-to-be-forgotten morning he finally agreed and told me: “We won’t lose too much if we limit it to a print run of two thousand.”

Now I became the book’s editor and assisted by my infinitely-patient friend Jean Slaven, I checked the long galley proofs to the last comma. There were five main sections: Historical Tales, Historical Embroideries and Lighter Tales, The Supernatural (Fairy Tales, Ghosts and Such, Strange Occurrences), Occasional Tales, and The Clearance of Strathnaver. Fifty-eight individual titles, more than a hundred stories. And when they came back from the publisher we checked the page-sized second proofs with the same infinite care.

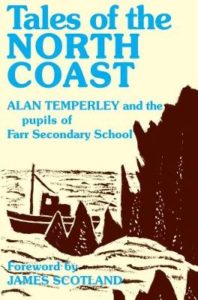

Spaces had been left for illustrations. Many dozen had been produced in woodcut-style by the pupils under the direction of their ever-enthusiastic art teacher Elliot Rudie. But they were not the right size so now, in those days before computers and printers, these were individually photographed in a make-shift darkroom beneath the school stage and reduced to millimetre-precise dimensions with a photographic enlarger. At length, with great anxiety, for none of us had done anything like this before, final text and illustrations were posted to the publisher in far-off London.

The finished copies arrived a few weeks later, hardback and paperback. They looked terrific: striking cover, 252 pages, top quality paper to take the solid blacks of the illustrations. It was an exciting time. The publisher had spoken of two thousand copies – they went in a week. Another two thousand went in a month. He published four thousand. Our book, in which no one had been interested, was a considerable success, reviewed in the national press and magazines, discussed on arts programmes, read by pupils on BBC regional radio, and has remained continuously in print – moving to a second publisher – for forty years.

Tales of the North Coast is loved in the area, and by those who visit the area, not for the quality of the writing, although I hope it is OK, but because it belongs to the area and the people. These are not my stories, they are theirs, and in no way have I embellished them. For the past decade sales have been small but now, with the impact of North Coast 500, many more people are travelling to the north and it occurred to me that there might be a case for a new edition. The idea was seized upon by Jim Johnston, who took over from me as English teacher back in 1973, became headmaster and has guided Farr to the status of a respected high school. He investigated what might be possible.

And now, precisely forty years after publication (1977 – 2017) a facsimile of the original paperback, backed by money from windfarms, has been published with the intention of keeping it in print indefinitely. I have said I want no royalties, being more interested in the book’s continued existence. 4000 copies have been printed, to be managed by the Strathnaver Museum in Bettyhill (known to many as the Clearances Museum), and profits will be divided between a fund for a new edition when hopefully this becomes necessary, and to support the growing museum itself. In May 2018 the museum hosted a re-launch celebration to which many of the original authors, sixty years old now, came from as far away as Golspie and Inverness. It was lovely to meet them again.

On a personal note, following the book’s success the publisher requested a follow-up and two years later I published Tales of Galloway, written entirely by me with seventies-style line illustrations by the pupils of Kirkcudbright Academy where I had recently been working. And because of my enduring love of north Sutherland I have published three novels, Murdo’s War, Huntress of the Sea, and Scar Hill, with the same setting.

Alan Temperley

June, 2018

To purchase Tales of the North Coast please contact:

Strathnaver Museum, Clachan, Bettyhill, Thurso, Caithness, KW14 7SS

Website : www.strathnavermuseum.org.uk/our-publications

Tel. 01641 521418

Email. info@strathnavermuseum.org.uk